In many workplaces, particularly those involving lone, remote or frontline work, employees often feel unsupported, unheard or unsafe. But these feelings aren’t just internal morale issues. They have real consequences for safety, mental health, incident reporting, and organisational performance.

The connection between safety, mental health and voice

When staff don’t feel they have a voice, or fear backlash from reporting incidents, a culture of silence takes root. Workers may underreport near-misses, hazards or aggressive behaviour, precisely the incidents that signal rising danger. Over time, that leads to unchecked risks, deteriorating conditions and safety failures.

This dynamic is especially dangerous in roles with inherent risk: home healthcare, social services, retail, utilities and inspections. Without psychological safety (the belief that you can speak up without retaliation), hazards go unnoticed until someone is seriously harmed.

Australian context: psychological injury on the rise

Data from Safe Work Australia shows that mental health conditions now account for around 9 % of serious workers’ compensation claims in 2021–22, a 36.9 % increase since 2017-18. The median time lost for psychological claims is more than four times longer than for physical injuries.

The National Baseline Report for Mentally Healthy Workplaces found that reported compensation for mental illness more than doubled over recent years, and workplace factors like poor voice (lack of feedback channels), unclear roles and low manager support are key contributors.

In the healthcare sector, the stress is even more visible. A recent study of over 11,000 Australian nurses and midwives revealed burnout, anxiety and depression as significant mental health outcomes tied to workplace demands. Meanwhile, frontline workers surveyed in the COVID era reported high psychosocial distress, including moral injury, fatigue, emotional exhaustion and reduced wellbeing.

These trends show that psychological risks are no longer secondary but they’re central to workplace safety and staff retention.

When staff don’t feel safe to report

A culture that doesn’t encourage reporting of incidents, such as harassment, aggression, near falls or hazards, is unfortunately common. Reasons include:

- Fear of retaliation or being blamed

- Lack of anonymity or confidentiality

- Belief that “nothing will change”

- Pressure to appear capable or resilient

- Low managerial support

When incidents go unreported, organisations lose essential early warning signs. A small pattern of threats may foreshadow a more serious event. Without data, risk assessments are incomplete, resource decisions are uninformed and interventions lag.

Moreover, staff who suppress concerns can experience guilt, moral distress, lowered trust and increased stress, all of which contribute to mental health decline.

The productivity and cost burden

Psychosocial harm doesn’t just hurt people. It hurts performance. The hidden costs include:

- Absenteeism and long leave due to psychological injury

- Presenteeism (being at work but not fully functioning)

- Turnover and recruitment costs

- Lower engagement, innovation and discretionary effort

- Loss of institutional knowledge and rising errors

As our previous article “The $15.8 billion wake-up call” argues, dissatisfaction and disengagement among frontline workers contribute to enormous financial drag. Supporting staff safety, mental health and voice isn’t a “nice to do” ; it’s critical to organisational resilience.

How to pivot toward supportive, safe workplaces

Below are practical levers organisations can apply to move staff from unsupported to empowered and safe:

1. Create psychological safety and feedback loops

- Encourage reporting with no-blame policies and anonymous channels

- Act on feedback visibly: show you listen and respond

- Train leaders to be accessible, empathetic and responsive

2. Embed safety tech and monitoring

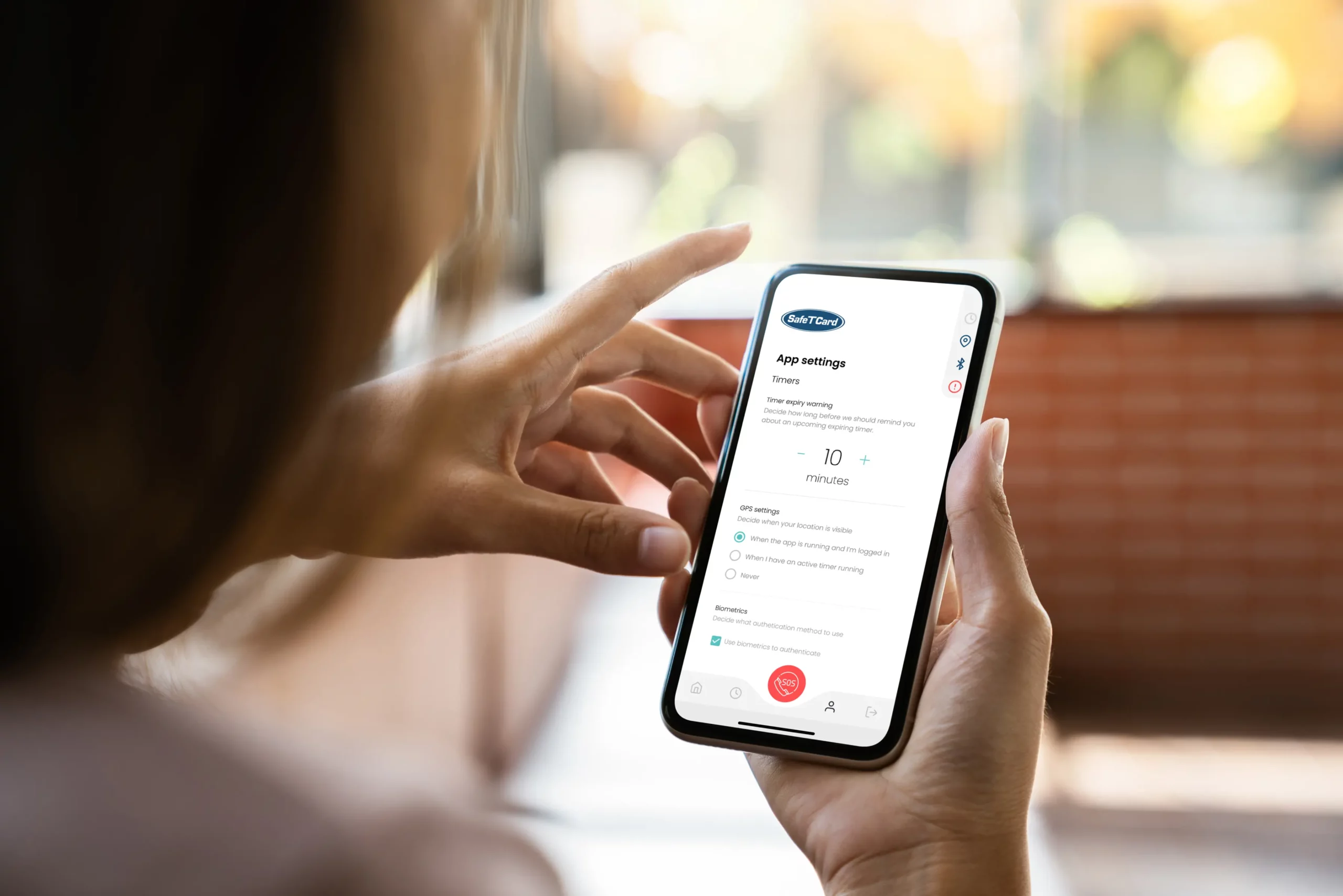

Use personal safety devices (lone worker safety devices, mobile apps, wearable SOS button) to give staff a real safety net. When workers know they have recourse, even in remote or isolated condition, it reduces the psychological burden of risk. Devices with two-way communication, automatic alerts (man-down) and audio check-ins (Yellow Alert) will make them feel supported even when they’re physically alone.

3. Integrate psychosocial hazards into WHS regimes

Treat harassment, work pressure, role ambiguity and lack of support as hazards equal to physical ones. Conduct dynamic risk assessments, include these in training, audits and incident reviews.

4. Build strong reporting and data practices

Track incidents, near-misses, grievances and hazard reports. Analyse them not to blame but to identify patterns, hotspots and systemic issues. Use that data to inform preventive measures.

5. Offer accessible mental health support

Provide EAPs, peer support groups, counselling, mental health training and resilience programs. Don’t silo these as optional perks. Integrate them into your safety framework.

Conclusion

When staff feel unsupported, unheard or unsafe, the consequences ripple: from mental health breakdowns to safety incidents and productivity decline. But there’s a path forward.

By creating psychological safety, embedding safety tools, valuing voice and feedback, and actively addressing psychosocial hazards, organisations can build workplaces where staff feel protected – physically and psychologically. Because safety isn’t just about preventing injury. It’s about enabling people to thrive, speak up, and return home whole.